The ethnic group Toraja, from the indonesian island of Sulawesi, is famous for their exquisite funeral rites and complex culture of death. And life. For them and their animist beliefs (called ‘aluk’, meaning ‘the way’) life and death are pretty much involved, and a funeral is a celebration, just another important step in anybody’s life. From all their rites and traditions, perhaps the most exotic part of their culture is the funeral itself, where they sacrifice buffalos and dress the dead relatives with new clothes and walk with these mummies along the village, a ritual called ma’nene that has to be performed in august, the typical funeral season.

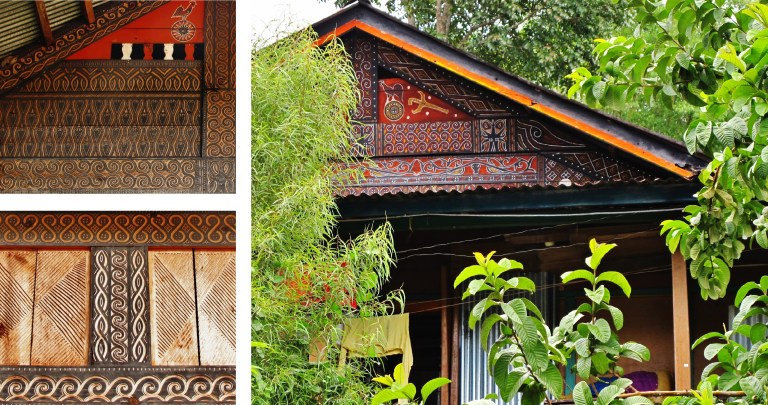

Toraja means people from the mountains. They live scattered in small villages in central Sulawesi and in a couple of towns nearby already developed for touristic purposes, being the most distinct feature of their landscape the curved roof of their traditional houses, called tongkonan. Homes for death poetically pointed towards the sky.

These houses, made from bamboo and with beautiful wood carvings painted with red, black, and yellow patterns, are used to keep a deceased person for some years in a period just after the death, when they believe the person is not totally dead but just going through a ‘passing away’ process until the moment of the proper funeral, where the person starts to ‘ascend’ to what they call puya, the land of the souls. This process can take as much as one decade, with the body staying in the traditional house until the family had saved enough money for the intrincate funeral rituals that the culture forces them to go through.

In villages on the mountains, the living and the dead co-exist together side-by-side (in, respectively, house on the right and house on the left).

The aesthetic of traditional houses permeates their everyday life, playing a big role in the pride they feel for their own culture. E.g. the patterns carved and painted on the walls of the houses for the death are sometimes also replicated in the homes of the respective families.

This aesthetical ‘contamination’ is present as well in small traditional houses in villages for keeping the rice, used in businesses and the urban landscape of the nearby town Rantepao, or as ornaments in people’s homes. In the land of Toraja death is everywhere.

Some local churches also exhibit the patterns in their architecture or decoration. Toraja people mix their own polytheistic animism with christianity, a legacy of the protestan missionaries from the old days.

In the funeral itself, called tomate, and after the dead bodies being taken out from the traditional houses, washed and dressed, they are taken for a walk along the village — in straight lines in order to follow Hyang, a spiritual entity who they believed always move this way. The whole celebration can take four or five days and the whole family, friends and neighbors are involved. Sometimes hundreds of people participate depending on the social position of the deceased person, and even tourists are welcome to join. They chant ma’badong, the music for the dead, perform ritual dances and organize buffalo fights, before slaughter them and divide the meat for all the guests. Pigs are also slaughtered and cock fights are held, being the spilling of blood on earth a crucial part on the whole sacred celebration.

In the funeral I attended some kids were playing with the chopped head of a buffalo, pressing its eyeball in with their little fingers while the rest of the people where happily eating and drinking around us, making the whole scene even more surrealistic.

The horns of the buffalos are then hanged on the traditional houses as a metric of the dead person’s social status.

The majority of population do farming for living, being a large part of their income dedicated to all the rituals related to death. For instance buffalos, which can be bought in Rantepao’s market, can cost up to 25 million rupees (around 1800 US dollars) for the common black species, which they typical have to kill around 10 to 20 in each funeral. For the albino buffalo people pay hundreds of millions, due to be considered more sacred and better for showing off the family status. Toraja people live poorly for being able to afford death.

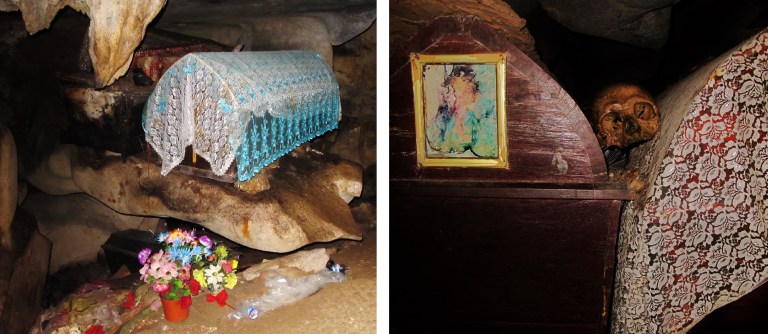

Typical coffins used by Toraja people.

Some of the ways they are placed for the final rest are in caves or hanged in cliffs, being the height correspondent to the social position of the deceased person (highlighted with a circle in a photo below). If the deceased is a baby, the tradition doesn’t involve a coffin and the baby is just wrapped in cloths and placed in a hole digged on a tree trunk, with the body and the tree slowly fusing together as the tree heals, both becoming one.

Nevertheless, the most common (and spectacular) way of burying the dead body is to dig a grave on a stone wall, typically with each hole being large enough to accomodate the whole family. At the entrance, a wooden statue of each dead relative is placed. Called tau-tau, they are the last vestige of the decease: the world of the dead looking to the world of the living, the world of the living always looking to death.

As the existential philosopher Martin Heidegger said, “If I take death into my life, acknowledge it, and face it squarely, I will free myself from the anxiety of death and the pettiness of life – and only then will I be free to become myself.”

It seems Toraja people are making his words come true quite literally; it’s the absolute culture of living the death.