A selection of pictures made for the World Health Organization through the NOOR photo agency, focused on showcasing the realities of accessibility and inclusivity of health care for people with disabilities in Cambodia, including access to care services not directly related with their disability — done in partnership with multiple CSOs on the field helping individuals achieving a more independent and dignified living conditions.

All Ears Cambodia providing testing and affordable access to hearing aid technologies. In picture, C.S., 73 years old, a patient with age-related hearing loss (Presbycusis), receiving free treatment at All Ears Cambodia. The NGO has different tiers according to the patient’s ability to pay the treatment, including at zero cost for anyone who can’t afford. Deafness is wide spread in Cambodia, having as main cause an easily-treated infection which often is first tackled by traditional medicine doctors using poor practices (e.g. inserting in the ear rat bile, crushed snails and gasoline) or relying on a unqualified pharmacist for healthcare advice. “The first person who is approached is not a doctor but often a pharmacist, who takes more of a role of business selling without prescription and no regulation. They shouldn’t be the first line of health consultation,” says Glyn Vaughan, the country director of All Ears Cambodia. “It’s seen as a low priority issue until it gets to a level of deafness that rocks the patient’s life, then becomes a high priority problem out of a sudden. (…) “The general population, especially marginalized groups and the really poor, need access to good quality health care. It’s a basic human right, it’s all about equity.”

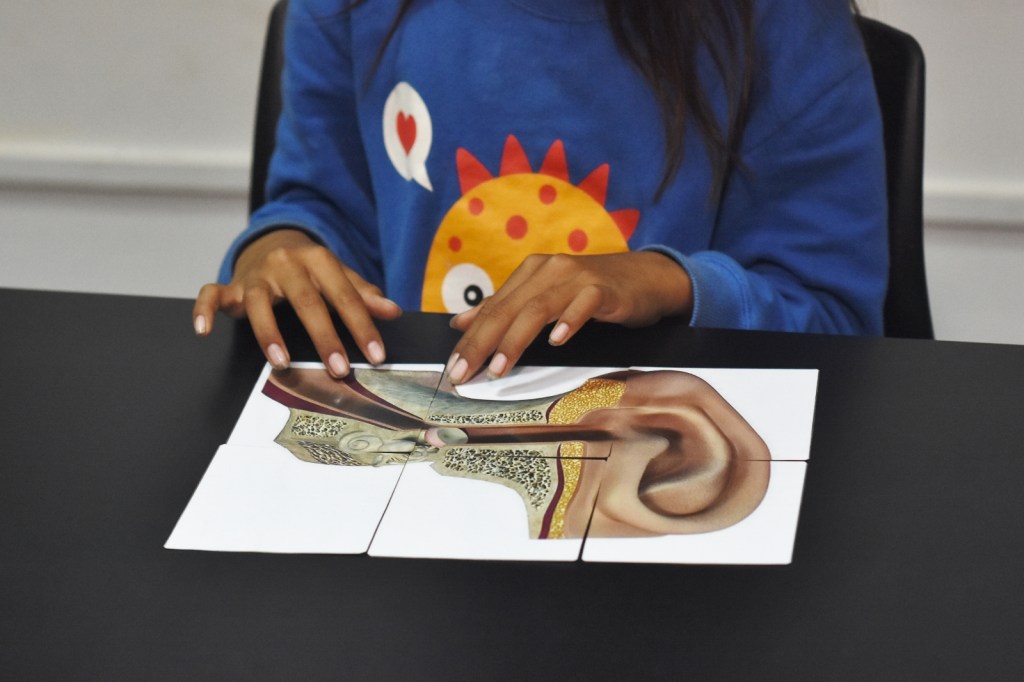

Classes for children about the importance of hearing health using games and music.

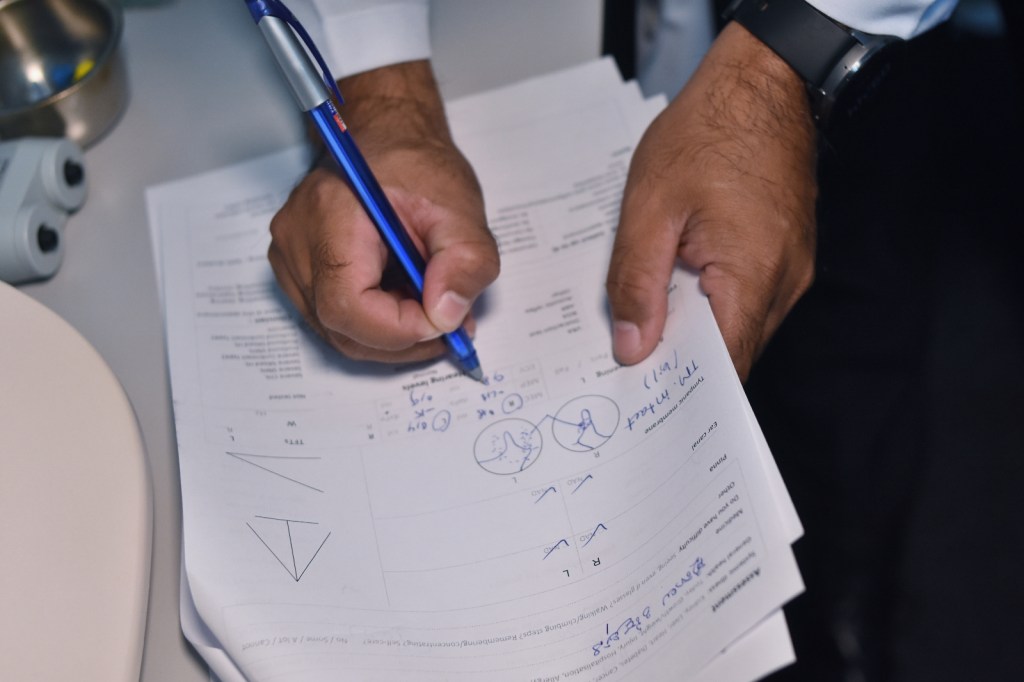

Affordable early testing services.

Sor Chuly, 10 years old, a beneficiary from One2One who was born with cleft palate. The NGO has a partnership with the Happy Dental Clinic in Phnom Penh to provide free follow-up visits after the multiple surgeries she received. Cleft lip and palate is one of the most common birth defects in Cambodia and, according to a 2018 study, only about 10% of children born with it receive surgery. The same study found that children with this condition in Cambodia are more likely to experience malnutrition, speech delays, and social isolation. Cleft lip and palate can also have a negative impact on a child’s education and employment opportunities.

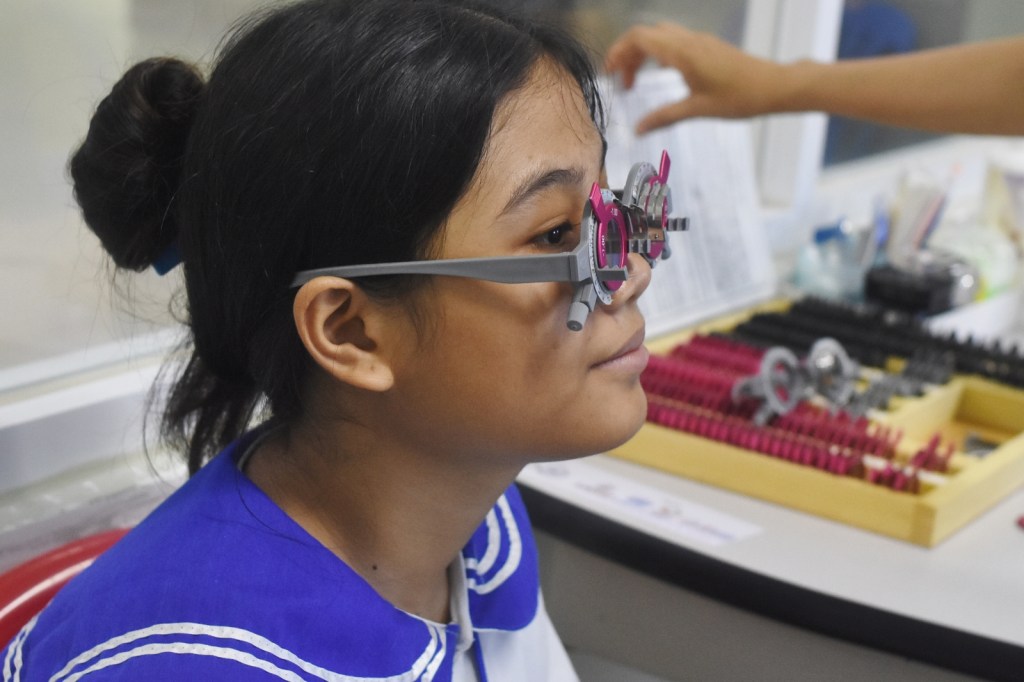

Sroeung Siv Mey visiting the Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital for en eyesight consultation. She is a deaf 16 years old who lives in the DDP school, a local NGO focused on education and Cambodia sign language. She is accompanied by Sok Dara, the school counsellor, to serve as interpreter, besides the NGO covering the cost of her glasses.

Graduating from the first grade did not enable her to read and write in Khmer. When the DDP program found her in her village, her parents did not want her to stay and study in the organization, thinking that their child could not learn like hearing people. The project brought Siv Mey’s parents to see in person the DDP office, accommodation, classrooms of the program, then the parents changed their minds by agreeing to encourage their child to receive educational services from the program. Siv Mey is happy that she has met and studied with many other deaf people, unlike when she lived in her village where she did not have friends to communicate with. Currently, she can read and write in Khmer language.

She started to noticed she was not able to see properly in classes, hence the visit to the hospital to get an eye consultation (provided for free from Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital) and get her first pair of glasses. The school counsellor was crucial to overcome the language barrier in the communication with the doctor, serving as interpreter throughout the process and also providing a helping hand in choosing the style of glasses she preferred. Now she is more confident to continue her studies and interact with her friends and classmates at the DDP school.

Residents of Kampuchea Sela H., a NGO providing essential services to people with cognitive disabilities, having fun learning how to skate in a weekly field trip they do to the skatepark in Factory Phnom Penh managed by the international NGO Skatistan. Access to safe environments to practice sports are fundamental for people with intellectual disabilities to develop self-confidence and managed their mental health.

The NGO has also partnerships with various organizations to provide access to important specialized health services such as dental care.

Residents of the NGO enjoying their weekly day of outdoor sports in a football field nearby the headquarters of the NGO Kampuchea Sela H. Many of their beneficiaries came from vulnerable backgrounds such as abandoned by their own families or rescued from human trafficking networks. Besides mental and cognitive development issues, they have a myriad of health conditions from skin to heart problems, besides the struggles during the pandemic years when 18 in 25 got infected with Covid-19 and couldn’t get vaccinated due to the lack of ID cards (70% of their residents, as most of their families didn’t registered them after birth and is a common issue the NGO has been battling with). Kampuchea Sela provides them with a safe haven not only for dignified living conditions but also activities such as farming and cooking what they grow, and access to sports such as in this case, in a collaboration with the local rugby team Kampuchea Balopp.

B. enjoying sports activities as part of the access to a holistic health program by the NGO Kampuchea Sela H., with rugby coach Dy Sophorn overseeing the exercises. It’s crucial for people with intellectual disabilities to be involved in a variety of activities to break the cycle of mistreatment and stereotype. Besides sports, the NGO also engages the residents in learning how to make jam as a tool for developing both motor skills and finding a sense of purpose and self-confidence through light work.

L. during a moment of comradery with his friends and fellow residents of Kampuchea Sela H. For people that since early age were rejected the inclusion in society, sports play an important role in their path of finding confidence and a sense of normalcy. “Often they are handle by a NGO since early age as families don’t even registered the child for ID card due to disability-related shame and taboos. The parents don’t want to have them in the family,”, says Valentin Dube, one of the full-time staffs in the NGO. They hold different workshops with parents to break stereotypes and stigma towards better inclusion, “we are trying to not have this responsibility forever, we believe that we should capacitate the family, in case they have, or the local community.”

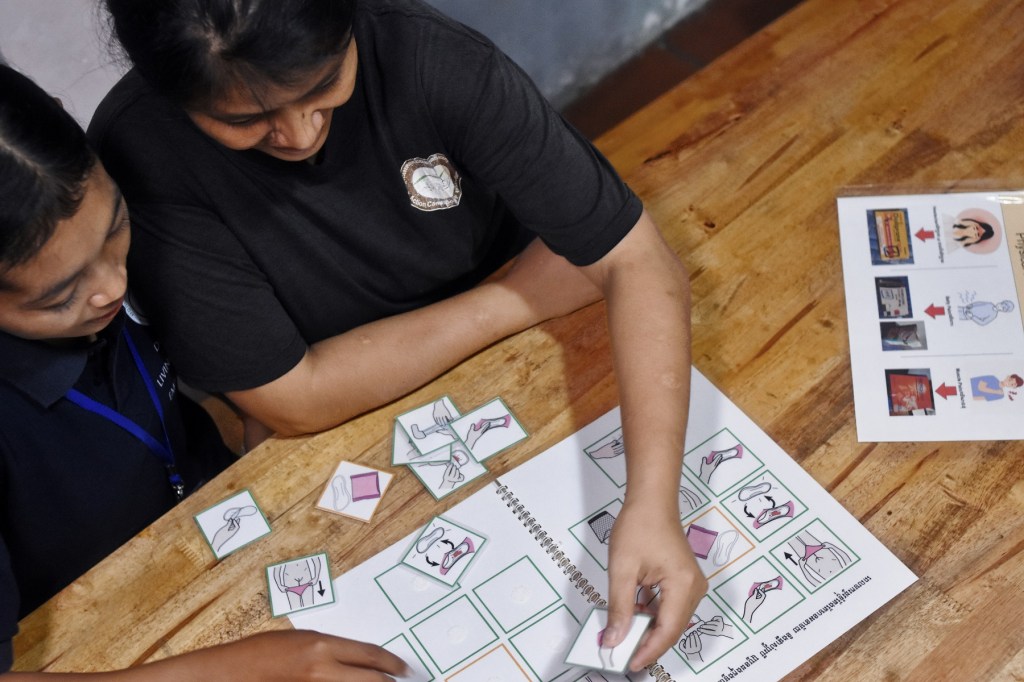

Sreypich, a staff member from Kampuchea Sela H., using some of IDP (individual development program) tools created in-house to talk with T. about practical everyday tasks. Communication using pictograms has been valuable for the NGO to increase understanding by their residents of a variety of activities, from asking if they brushed their teeth, took shower or feel hungry, to pointing to pictures of other residents and staff members when they want to call for someone. These tools have been developed in collaboration with the residents and adapted to their needs and level of cognitive capacity.

Sreypich, a staff member from Kampuchea Sela H., using some of IDP (individual development program) tools created in-house to teach P. about menstruation. Communication using pictograms has been valuable for the NGO to increase understanding of various health-related issues faced by their residents.

K., a young woman with speech disorder and cognitive development issues, going to the pharmacy to buy paracetamol for a headache. To overcome communication issues with the pharmacist, Kampuchea Sela H. provides various picture-based sheets focused on the most common conditions and required medicines, in addition to pictograms describing usage (e.g. how many pills per day, to take by morning or by night, etc.) “There is a problem of access [for individuals to easily access medication] and they do not provide any indications or prescription, just a small bag with assorted pills, no tablet with information on expiration date or indication of how many pills to take per day, it is really not safe,” says Valentin Dube, one of the staff members, who stresses the lack of understanding of health professionals and adapting language to people with disabilities. “Every time we go to a hospital is very difficult to get a prescription to know what to take, or to use for follow-up on the treatment.”

The organization Phnom Penh Center for Independent Living has various mobility vehicles that people with disabilities can call to help achieving a more normalized everyday life.

Heang Horn and Dara Kheng with their respective personal assistants, going to buy vegetables in a street shop near their home. Various PwD supported by PPCIL live in the same neighborhood of the NGO and have their P.A. providing essential care at home such as cooking and daily hygiene.

Heang Horn who, besides a spinal cord injury from a motorbike accident who made him bound to a wheelchair, had to go through an urostomy procedure due to bladder issues. The personal assistant provided by the Phnom Penh Center for Independent Living plays a crucial role in assuring he follows his daily medication or eats healthy meals, enabling him to live a normal life

Heang Horn (front) and Dara Kheng (back), with their respective personal assistants provided by PPCIL, going home. Phnom Penh, with its lack of sidewalks and comfortable design, often poses safety risks to wheelchair users and forces them to move amidst the traffic.

Haseka Poeng, from Kampong Cham province, in her current home in Phnom Penh. Born unable to move both her legs and with partial mobility in her hands, she was able to get educated at home by her mother and ended up getting a job in the NGO Phnom Penh Center for Independent Living. “We would like to have more personal assistants from the government to be able to go outside and do activities, not just stay at home. Only in Phnom Penh we have them because of PPCIL but what about in the countryside?”

Haseka Poeng using a ramp in a recent building in Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital, a good example of inclusive design. In terms of accessibility ramps are becoming the new normal, although often without standards to be easily used. “Sometimes people think that having a ramp and rail in the entrance is enough,” says Mey Samith, director of PPCIL, “but without properly designed toilets or front counter in reception with appropriate height then it’ll become difficult [for a PwD] to interact with doctors or nurses”. She arrived to the hospital using one of the PPCIL accessible vans, the NGO has four accessible vans (from a total of five in Phnom Penh, no data on the availability of similar vehicles in other provinces) in addition to some adapted tuktuks available for hire made in collaboration with a local social enterprise.

Haseka Poeng waiting for a check-up as she suffers from thyroid issues and goiter disease. Access to mainstream healthcare is crucial for people with disabilities, and the recent Equity card and NSSF program are examples of implementations on the right direction. Nevertheless, people with disabilities still face various challenges accessing healthcare, including lack of understanding from doctors about their issues, or a common fear from health professionals that a PwD will not be able to afford the consultation.

The different buildings present in the hospital present a variety of accessibility features considering the year they were built.

Thythou Pham, 65 years old from Kandal province, receiving a monthly follow-up consultation in St. Elizabeth Sick Center for managing various indicators such as glycemia and blood pressure under the care of Dr. Pav Sochinda. The center provides free diagnosis for people living under the poverty line and refers to public hospitals when needed, besides having resident cancer, diabetes, thyroid and hypertension patients. Many of their elderly patients aren’t able to receive IDPoor card for various reasons, so the center provides from 70 to 100% of their healthcare expenses, besides doctors and nurses to accompany them to the hospital and/or provide palliative care in-house. A common issue with many of their patients is the lack of social networks and family care, as migration for finding work in their low income neighborhoods is fairly common. The center provides them with psychological counselling and entertainment activities such as trips to the pagoda, royal palace or the shopping mall, preferring to see their role as more holistic than purely diagnosis and treatment.

Put Hin, a 61 years old construction worker, receiving a diabetes follow-up consultation in St. Elizabeth Sick Center. Complaining about numbness of legs, Dr. Pav Sochinda provides him with advice for a healthy diet and exercise, in addition to meditation before sleeping as he struggles with his mental health. From Takeo province, in his village other people died from diabetes due to not being able to afford going to the clinic. Luckily he got to know this center in 2015 and has been coming for free follow-up appointments since then. A common issue mentioned by Dr. Pav Sochinda with low-paid workers such as him is the consuption of energy drinks, besides lack of enough money for a balanced diet. In addition of medicine for controlling his diabetes, he receives a prescription for hypertension, colesterol, and anticoagulant, being advised to not rely solely on traditional medicine, a common practice in his village.

Voeng Thy Your, 68 years old, a cervical cancer patient from Russei Keo, Phnom Penh. She is half way through her chemotherapy treatment (three more appointments, receiving surgery afterwards) and also suffers from hypertension and diabetes. Not being able to receive proper care and nutritious meals at home, after each round of chemo in Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital she stays one week in St. Elizabeth Sick Center in order to be monitored and supported. Some of their patients can stay in stay in the center up to eight months, besides being supported with $4000- to $6000 as IDPoor card doesn’t cover chemotherapy treatment.